Thursday, October 4, 2012

The Fall of the Roman Republic,

I. The Stress of Imperialism

A. The Failure of the Republic--the success of the empire project unleashed factors that lead to the end of the Republic. Most of the wealth generated by the near constant state of warfare and conquest flowed to the wealthiest, while impoverishing small farmers in the countryside. While the male head of household was off fighting, his family often became impoverished, being forced to sell their land and move to the city.

1. Social dislocation--the impoverished masses were eventually recruited to serve in the Roman army--but their dependence upon the largess of their generals meant that their primary loyalty was to them, rather than to Rome, and the army was used be a series of individuals to seize control of the government. During the early years of the Roman Republic, wars were relatively brief, and the farmers who made up most of the soldiers were away from their homes for relatively short times. As warfare grew more constant, and lasted longer, farmers were away from their farms and families for longer periods of time--and forced to leave their wives to run these farms in addition to other duties.

2. The Poor--for a variety of reasons--the fact that the rich were obtaining ever more land, and a sudden increase in birth rates, land became more scarce and expensive. As a result, more people moved into Rome; perhaps as many as 500,000 people lived in the city of Rome by 200 B.C.E. This was more people than the city could provided jobs for, leaving some to beg in the streets, and forcing many women into prostitution. The landless poor in Rome became an explosive swing-element in Roman politics, willing to follow those leaders who promised them a better economic situation. By the late second century B.C.E., Rome needed to import flour to feed its population, providing the poor with free bread--which became one of the most divisive issues in late republican politics

3. The Rich--while the landless poor struggled, imperialism brought Rome's economic elites ample political and financial rewards. At first, this wealth was plowed into public works that benefited the general population--temples, forums, coliseums. With increased economic disparity, however, the rich also began to concentrate more on ways the could display their wealth privately, by building ever more opulent homes, and throwing ever more lavish parties to impress their other rich friends and win themselves greater esteem--a rejection of the way that Romans had previously gained more esteem by their simple lives.

II. Civil War and the Destruction of the Republic

A. The Gracchus Brothers and Violence in Politics, 133-121 B.C.E.--though born to a rich patrician family, the Gracchus brothers rose to political prominence pressing their rich peers to make concessions to strengthen the state.

1. Tiberius Gracchus--elected tribune in 133 B.C.E. and immediately ignored the Senate's advice and convinced the Plebeian assembly to pass laws to redistribute land to landless Romans. The next year, Tiberius made the unprecedented announcement that he would stand for election as tribune for a second year, but his cousin led a group of Senators he clubbed Tiberius and many of his followers to death.

2. Gaius Gracchus--elected tribune in 123 B.C.E.--and, contrary to tradition, again the following year--he also pushed for reform measures that outraged the elite: farming reforms, subsidized prices for grain, public works projects to employ the poor, and colonies abroad with farms for the landless.

a. Perhaps Gaius' most important reform were measures that granted many Italians Roman citizenship, and the creation of courts with equite jurors to try Senators for wrongdoing--which meant that the equites would be social equals to the patrician Senators. The Senate move to block this legislation, and Gaius assembled an armed group the threaten them. The Senate then advised consuls to take all measures necessary to protect the Republic, meaning themselves, and the consuls set off to kill Gaius. He cheated them of that prize, committing suicide by slave

B. Marius and the Origins of Client Armies, 107-100 B.C.E.--The republic needed innovative military commanders to combat slave revolts and foreign invasions in the late second and early first centuries B.C.E. The "new men" who rose to meet this challenge relied upon sheer ability--and often political violence--to force his way to fame, fortune, and the means of gaining those, the consulship.

1. Gaius Marius (c. 157-86 B.C.E.)--Marius came from the equites class, and set the pattern fro this new kind of leader. Previously, he would have had no chance to become consular, but his military prowess as a young officer, and continued success in the military, led to his being voted a triumph, Rome's ultimate military honor--and he was able to use the support of the common people of Rome to move up politically

a. Opening the ranks of the army--previous to Marius, only men of some property could become members of the Roman Legion. Marius opened the ranks to the propertyless proletarians, which gave them the opportunity to gain wealth and property. This also meant that proletarian troops felt a great deal of goodwill toward their commander, and began behaving like clients following their commander as a patron. Marius was the first to promote his own career this way, but he would be followed by men more ruthless than he was.

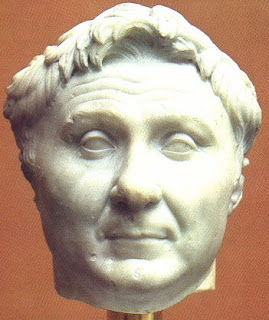

2. Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138-78 B.C.E.)--took advantage of uprising by non-Romans in Italy and Asia Minor to use his client army to seize Rome's highest offices and force the Senate to support his policies. His career revealed that politics in the late Republic prized individual advancement over peace and the good of the community.

a. The Social War--non-Romans had no vote in decisions concerning their own interests, and chose to ally together to fight Rome. Although the allies lost the battle--and 300,000 men--they won the war, because Rome granted citizenship to everyone living south of the Po river (the traditional northern boundary of Italy)

b. Plunder abroad and Violence at home--Mithradates IV took advantage of discontent with the exorbitant tax rates the Romans were collecting in Asia Minor to convince people there to kill all the Italians--tens of thousands of them--in a single day. In retaliation, the Senate voted to send a military expedition to punish this act. The riches promised by the ability to plunder much of Asia Minor made this a plum assignment, which was given to a member of a patrician family, Sulla. Marius attempted to seize the assignment through a plebiscite; Sulla responded by marching his army on Rome, he allowed his men to rampage through the city, killed many of his enemies, and left it in a state of civil war while he marched off to Asia Minor to fight and plunder there. Civil war raged in Rome for two years, while Sulla enriched himself in Asia Minor; he returned to Rome, put down the civil war, then attempted to eliminate the rest of his enemies by proscription.

3. Gnaeus Pompey--rose to prominence when he was able to parlay the mop-up operation against the slave uprising led by Spartacus into greater fame by portraying it as the decisive battle. He demanded and received a consulship even though the had none of the qualifications. He led a successful operations against Mithradates, and a spectacular one against pirates in the Mediterranean. In 64 B.C.E., Rome annexed, and Pompey ended the Seleucid kingdom and brought the eastern Mediterranean under Roman control

4. First Triumvirate--the Senate attempted to block Pompey, who they viewed as being too powerful. Pompey therefore turned to his most powerful political rivals, Crassus and Julius Caesar, and formed the First Triumvirate. Pompey controlled much of Italy, Crassus Asia Minor, and Caesar the area in present-day southern France then known as Gaul. To cement their political relationship, Caesar gave his daughter Julia to be Pompey's wife (Pompey had divorced his wife, who rumor had it had been seduced by Caesar).

5. Civil War--with Julia's death in childbirth in 54 B.C.E., the fragile peace between Caesar and Pompey broke down, and armed gangs backing the two men fought each other in the streets of Rome; the violence grew so bad that elections could not be held. When the Senate demanded that Caesar surrender his command, he crossed the Rubicon with his army to invade Rome. Caesar was wildly popular with much of the citizenry in Italy, who expected him to follow his usual practice of handouts for the impoverished. Pompey and Caesar's other enemies fled Rome for Greece in response. Caesar and this troops then defeated the army under Pompey, who then fled to Egypt, where he was murdered by the counselors of the teenaged Ptolemy XIII. Caesar next invaded Egypt, winning a difficult campaign there when he restored his lover Cleopatra VII to the throne.

6. Caesar's Dictatorship and Murder--Caesar apparently concluded that only one man--him--could end the bloodshed that Rome had fallen into. He declared himself "dictator" (a position that was proclaimed by the Senate during times of crisis--although he essentially ruled as a king. His policies were meant to improve the financial situation and reward his supporters; he offered them a moderate cancellation of debts, a cap on the number of people eligible for free subsidized grain, a large program of public works, citizenship for more non-Romand, and plans to rebuild Corinth and Carthage as commercial centers. This angered the optimates, who viewed him as a traitor, and some senators, led by Caesar's former close friend Marcus Junius Brutus, stabbed him to death in the Senate.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment